How Mobile Phones Really Work: The Complete Guide to Cellular Networks in the UK (2026)

By Richard – Mobile phones are ubiquitous—but behind their seemingly effortless operation lies a complex cellular network ecosystem that most people never think about. In this article, I take you on a deep dive through the technology that makes mobile communication possible, with a particular focus on the UK context. We’ll explore how phones find their location without GPS, the evolution from 2G to 5G, the structure of network providers, how you stay connected when roaming abroad, security protocols, the business of spectrum auctions, and much more. By the end, you will understand not just what is happening when you make a call, but the incredible engineering that makes it all possible.

What this comprehensive guide covers:

- How phones triangulate their location without GPS (and why it matters).

- The evolution from 2G to 5G: speeds, frequencies, and real technical differences.

- UK mobile network providers: the four MNOs and hundreds of MVNOs.

- How your SIM card authenticates you on the network.

- Understanding data roaming and international connectivity.

- Embedded SIMs (eSIMs) and the Internet of Things.

- The UK spectrum auction process and how much operators pay (with December 2025 data).

- Network infrastructure: masts, small cells, and backhaul.

- Network protocols and standards: GSM, UMTS, LTE, NR.

- Coverage distances: why 2G reaches 20km but 5G covers hundreds of metres.

- Security, privacy, and encryption.

- The history of UK mobile networks (Vodafone 1985 to VodafoneThree 2025).

- Common myths busted with real evidence.

- Complete FAQ and technical glossary.

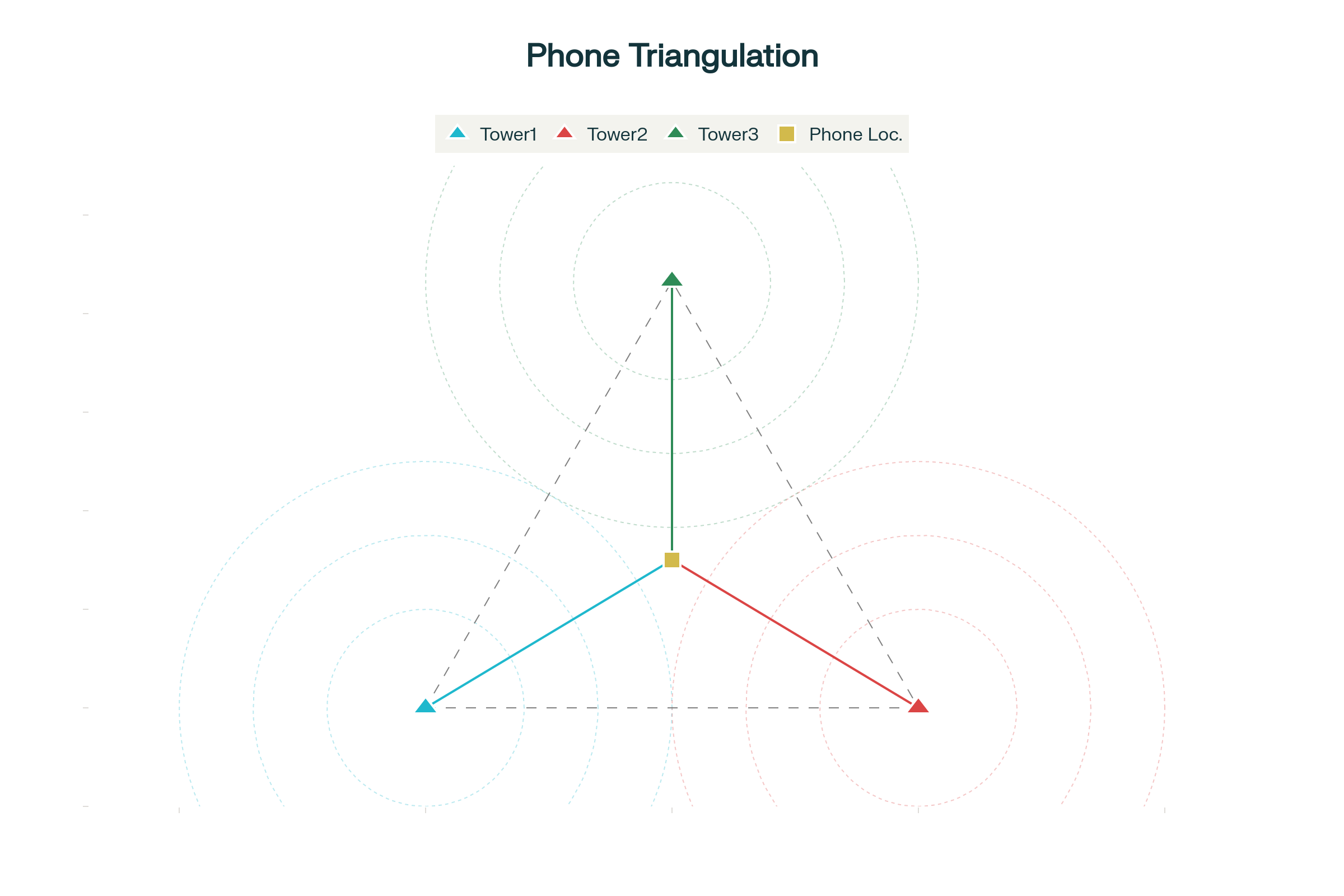

1. How Phones Find Themselves: Triangulation Without GPS

When you think about how your phone knows where it is, you probably think of GPS. But there is another system running silently in the background: cellular triangulation. This is how your phone can pinpoint its location even when GPS fails, and how emergency services can find you when you dial 999.

The Triangulation Method:

Your phone communicates with multiple nearby cell towers simultaneously. Each tower measures the signal strength of your phone’s transmission and calculates the distance based on how weak the signal has become. By knowing the exact location of at least three cell towers and the distance from each one to your phone, the network can triangulate your position—essentially solving a geometric problem.

Real-world accuracy:

- In dense urban areas (like London): 50–200 metres accuracy

- In suburban areas: 200–500 metres accuracy

- In rural areas: 500–2,000 metres accuracy (depending on tower density)

The accuracy depends on three factors:

- Tower density: More towers nearby = more precise triangulation

- Signal quality: Clear line of sight to towers improves measurements

- Frequency band used: Lower frequencies (like 800 MHz) reflect off buildings, making measurements less accurate; higher frequencies provide cleaner signals

✓ Why This Matters: When you dial 999 in the UK, the emergency service does not rely on GPS (your phone might be indoors where GPS does not work). Instead, it uses cellular triangulation combined with your phone’s IMSI number to locate you within minutes. This has saved thousands of lives.

Assisted GPS (A-GPS):

Modern phones combine GPS with cellular data. Your phone’s GPS gets a “heads start” by downloading orbital data from the network, which reduces the time to get a position lock from several minutes to seconds. This is called Assisted GPS or A-GPS. It is why your phone’s location works so quickly when you open Maps.

2. The Evolution: 2G to 5G (And Why Each Generation Matters)

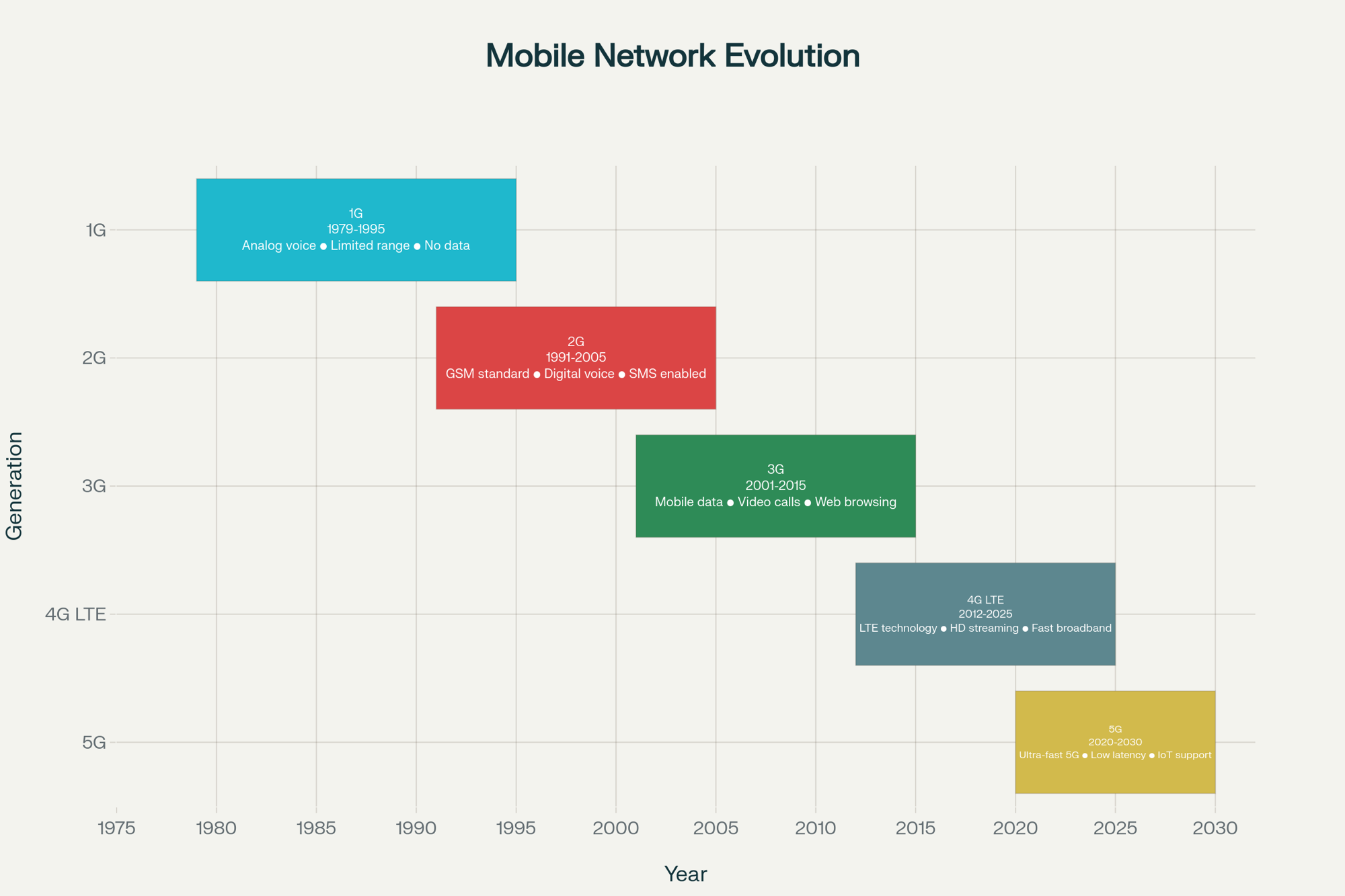

Mobile network technology has evolved through five distinct generations, each offering massive improvements in speed, capacity, and capability. Understanding these generations is key to understanding what your phone can and cannot do.

2G (GSM): The Digital Revolution (1991–Present)

- Technology: Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM)

- Launch in UK: Early 1990s (Vodafone and Cellnet)

- Frequencies: 900 MHz and 1800 MHz

- Data speed: 9.6 kbps (initially); evolved to 56 kbps with GPRS

- Primary use: Voice calls and SMS text messages

- Coverage distance: Up to 20 km in rural areas (due to low frequency)

- Status: Being phased out; UK providers shutting down 2G networks by 2030

Why 2G matters today: Many older devices still rely on 2G. When UK networks shut down 2G, millions of devices will stop working—from emergency call buttons in care homes to ATMs in remote areas. This is a massive infrastructure challenge happening in real time.

3G (UMTS): The Mobile Internet Era (2003–Present)

- Technology: Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS)

- Launch in UK: 2003 (all four major operators)

- Frequencies: 2100 MHz (primarily)

- Data speed: 2 Mbps (theoretical); typically 384 kbps to 1 Mbps real-world

- Primary use: Mobile internet, email, basic video calling

- Coverage distance: 1–3 km in urban areas; 5 km in optimal rural conditions

- Status: Being phased out; UK operators shutting down 3G by 2032

Interesting UK fact: Three (originally called “3”) never launched a 2G network. They started directly with 3G in 2003, which is why their name is literally the generation they launched with. This was a bold move at the time—it meant they could only target customers with 3G handsets—but it became a key part of their brand identity.

4G LTE: The Smartphone Era (2012–Present)

- Technology: Long-Term Evolution (LTE)

- Launch in UK: 2012 (EE first, followed by others)

- Frequencies: 800 MHz, 1800 MHz, 2600 MHz (and others)

- Data speed: 100 Mbps (theoretical); typically 20–50 Mbps real-world; up to 1 Gbps with LTE-Advanced

- Primary use: HD video streaming, social media, gaming, video calls

- Coverage distance: 2–5 km depending on frequency band

- Status: Dominant network across the UK; will remain for 15+ years

Why 4G was revolutionary: 4G made YouTube, Netflix, and Instagram possible on mobile phones. It transformed mobile from a communication device into an entertainment and productivity device. Every major app you use today was built assuming 4G speeds.

5G (NR): The Future (2019–Present)

- Technology: New Radio (NR)

- Launch in UK: 2019 (EE first, rolling out across all operators)

- Frequencies: Sub-6 GHz (600 MHz, 2.1 GHz, 3.5 GHz) and mmWave (26 GHz, 40 GHz)

- Data speed: 1–10 Gbps (theoretical); 100–500 Mbps real-world in good coverage areas

- Latency: 1 millisecond (versus 50ms on 4G)

- Primary use: 8K video, augmented reality, IoT, autonomous vehicles, remote surgery

- Coverage distance: Sub-6 GHz: 1–3 km; mmWave: 100–300 metres

- Status: Rapidly rolling out; December 2025 auction added significant new capacity

⚠️ Important 5G reality: While 5G is impressive on paper, coverage in the UK is still patchy outside major cities. The high-frequency bands (especially mmWave at 26 GHz and 40 GHz) have very short range and require small cells in every city block. This is expensive to roll out, so most rural areas will not see 5G for years. If you are outside a major city, 4G will likely remain your primary network for the foreseeable future.

Comparison Table: Key Differences

| Generation | Primary Frequency | Speed (Real-World) | Coverage Distance | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2G (GSM) | 900 MHz, 1800 MHz | 56 kbps | Up to 20 km | Voice, SMS |

| 3G (UMTS) | 2100 MHz | 1–2 Mbps | 1–5 km | Mobile internet, email |

| 4G (LTE) | 800, 1800, 2600 MHz | 20–50 Mbps | 2–5 km | Video streaming, social media |

| 5G (NR) | Sub-6 GHz, 26 GHz, 40 GHz | 100–500 Mbps (sub-6 GHz) | 1–3 km (sub-6 GHz) | AR/VR, autonomous vehicles, IoT |

3. UK Mobile Network Operators: The Big Picture in 2025

The UK mobile landscape changed dramatically in June 2025 when Vodafone and Three merged to create VodafoneThree—the largest mobile network operator in the UK by customer numbers. This left a three-player market rather than the previous four.

The Three Major Network Operators (MNOs):

- EE (part of BT Group): ~34 million customers; strongest 5G coverage; earliest to launch 4G and 5G

- O2 (part of Virgin Media O2): ~33 million customers; strong nationwide coverage; recent spectrum acquisitions for 5G expansion

- VodafoneThree (merged June 2025): ~27 million customers; now the largest by customer count; pledged £11 billion for 99% 5G coverage by 2034

Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs):

Beyond the three major operators, there are hundreds of MVNOs that lease network access from the MNOs and resell it under their own brands. The UK MVNO market reached £5.23 billion in 2025 and is growing at 7.3% annually, according to Mordor Intelligence.

Major UK MVNOs include:

- Tesco Mobile: Highest brand recognition; uses O2 network; attracts budget-conscious customers

- Sky Mobile: Sky Broadband customers; uses O2 network

- Giffgaff: Community-driven; uses O2 network; known for flexible pricing

- Lycamobile: International focus; discounted international calling

- Lebara: Immigrant communities; competitive international rates

- Smarty: Roll-over data; no expiry dates; innovative pricing model

- iD Mobile: No-frills; basic plans; recently expanded data offerings

- Revolut: FinTech company; bundled banking + mobile services

✓ Why MVNOs Matter: MVNOs create competition that drives down prices and increases innovation. Because they do not own infrastructure, they can take risks that MNOs cannot. Many of the best pricing innovations (like Smarty’s roll-over data) come from MVNOs first, then get copied by MNOs. The UK MVNO market is one of the most competitive in Europe.

4. How You Stay Connected: SIM Cards and Authentication

Every time you turn on your phone, it performs a complex authentication ritual with the network. You never see this happening, but it is essential to how mobile communication works.

The SIM Card: Your Digital Passport

Your SIM (Subscriber Identity Module) card contains:

- IMSI (International Mobile Subscriber Identity): A 15-digit unique identifier that identifies you on the network

- IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity): A 15-digit identifier for your specific phone (stored in the phone’s hardware, not the SIM)

- Authentication key (Ki): A secret key shared with the network that proves you are authorized

- Operator information: Details about your network provider and billing account

How Authentication Works:

When you switch on your phone:

- Your phone broadcasts its IMSI to the nearest cell tower

- The tower forwards this to the network’s authentication server

- The server sends a random challenge to your phone

- Your SIM uses its secret key to compute a response to the challenge

- The network checks if the response is correct

- If it matches, you are granted access; if not, you are denied service

This happens in less than 2 seconds, and your phone does it every time you move to a new cell tower. It is a cryptographic handshake happening thousands of times per day across the UK.

eSIM: The Future of SIM Cards

eSIMs (embedded SIMs) are not physical cards—they are rewritable chips built into your phone. You can switch networks by downloading new profile data, without physically swapping SIM cards.

Advantages of eSIM:

- Seamless network switching (useful for international roaming)

- No physical SIM slot needed (saves space in phones)

- Faster provisioning (activation in minutes instead of hours)

- Multiple profiles on one device (e.g., work and personal numbers)

Current adoption in the UK: About 25% of new phones sold in 2025 are eSIM-capable. By 2028, this will reach 58%, according to Mordor Intelligence. Vodafone and others are pushing eSIM adoption through faster activation and lower costs.

5. Data Roaming: How Your Phone Works Abroad

When you travel abroad and your phone connects to a foreign network, something remarkable happens: you stay connected to your home network’s billing system while using foreign infrastructure.

How Roaming Works:

- Your phone lands in a foreign country and searches for available networks

- It finds a local network with a roaming agreement with your UK provider

- Your phone sends its IMSI to the foreign network

- The foreign network contacts your home network to verify you

- Your home network authenticates you and says “Yes, this customer is real”

- The foreign network grants access and bills your home network for the traffic

- Your home network bills you for the usage

Brexit and Roaming Changes:

Before Brexit (2020), roaming within the EU was free or very cheap for UK customers. Post-Brexit, this changed. Most UK operators now charge roaming fees for EU use, though some offer “Roam Like Home” packages where you pay the same price as in the UK.

Example (December 2025): EE charges £2/day for roaming in the EU (automatic daily passes). Vodafone has similar pricing. Three offers higher allowances (500 MB free daily, then paid overage). Compare rates before traveling.

Emerging Technology: Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN):

In remote areas where terrestrial networks do not reach, new satellite-based systems are coming. O2 demonstrated this in Northumberland in January 2025 using Starlink links to deliver 4G coverage. By 2027–2028, phones with NTN capability will be able to roam between terrestrial 5G and satellite networks seamlessly.

✓ Pro tip: Before traveling, contact your network provider to understand roaming costs. Many providers offer travel passes (e.g., “30 days in Spain for £30”) that are far cheaper than pay-as-you-go rates. Always check.

6. Network Infrastructure: The Physical Foundation

Behind every call and data transmission is a vast physical infrastructure. Let’s break down the key components:

Cell Towers (Base Stations):

- What they are: Towers with antennas that broadcast cellular signals

- Coverage area: Depends on frequency (see coverage distances section below)

- Power consumption: A typical macro cell tower (macrocell) consumes 4–10 kW continuously

- Placement: Rooftops, dedicated poles, church steeples, water towers, etc.

Small Cells:

- What they are: Low-power base stations (femtocells, picocells, distributed antenna systems)

- Coverage: 100 metres to 1 km radius

- Why they matter: 5G requires massive numbers of small cells for coverage because high-frequency signals (26 GHz, 40 GHz) do not travel far

- UK deployment: Major cities are seeing small cell deployment in 2025; rural areas still lag

Fiber Optic Backhaul:

Data from cell towers does not magically fly through the air to the internet. Instead, fiber optic cables (backhaul) connect towers to regional network hubs, which connect to national hubs, which connect to the internet. This backhaul is often the bottleneck for network performance.

Real example: A tower in central London is connected via fiber to EE’s London hub. That hub is connected via high-capacity fiber to EE’s national core network in London. All of this is underground, invisible, and heavily engineered for redundancy.

Network Core:

The network core is the “brain” of the system. It handles:

- Routing calls and data to the correct destination

- Billing (tracking every MB you use)

- Authentication (verifying you are who you claim to be)

- Roaming coordination (handling your data when you travel)

- Quality of Service (ensuring video calls get priority over email)

4G networks use the EPC (Evolved Packet Core). 5G networks use a new architecture called the 5G Core (5GC), which is more flexible and supports network slicing (dedicating virtual sub-networks to specific applications).

7. Spectrum Auctions: The Business of Radio Frequencies (December 2025 Update)

Mobile networks do not just appear—operators must bid for spectrum (radio frequencies) at government auctions. The UK government runs these auctions, and the amounts of money involved are staggering.

Most Recent: October 2025 mmWave Auction

In October 2025, Ofcom (the UK’s communications regulator) conducted an auction for millimeter-wave spectrum (26 GHz and 40 GHz) intended to boost 5G capacity in high-traffic urban areas.

- Total revenue raised: £39 million

- Winners: EE, O2, and VodafoneThree (each won equal allocations)

- Allocation: Each won 800 MHz in the 26 GHz band and 1,000 MHz in the 40 GHz band

- Price per operator: £13 million each

- Deployment areas: 68 towns and cities (football stadiums, concert venues, transport hubs)

The reason the auction raised relatively modest revenue (compared to earlier 3.5 GHz auctions that raised £1.35 billion in 2022) is that mmWave spectrum is less valuable—it has shorter range and is harder to deploy. But it is valuable for capacity in specific high-traffic areas.

Earlier Major Auctions:

- 2022 (3.5 GHz spectrum): £1.35 billion total; operators competed heavily for prime spectrum bands

- 2021–2022 (4G spectrum re-farmed): Significant investment in lower-band spectrum for coverage

- June 2025 (Virgin Media O2 acquisition): VMO2 acquired 78.8 MHz of spectrum for £343 million, bolstering capacity

⚠️ Why This Matters to You: Every pound operators spend on spectrum auctions is eventually passed on to consumers through higher tariffs. When Vodafone and Three spent billions on spectrum over the years, that cost gets absorbed into what you pay for your mobile plan. Competition and spectrum availability directly affect your monthly bill.

8. Coverage Distances: Why Generations Have Different Range

One of the most confusing aspects of mobile networks is understanding why 2G reaches 20 km but 5G mmWave covers only a few hundred metres. The answer lies in physics and frequency bands.

2G (GSM): The Long-Range Champion

Frequency: 900 MHz and 1800 MHz

Coverage distance: Up to 20 km in open rural areas (ideal line of sight)

Why so far? Lower frequency signals have longer wavelengths (about 30 cm for 900 MHz). Longer wavelengths diffract around obstacles better, meaning they bend around hills, buildings, and trees. This is why 2G coverage works in rural areas where later generations struggle.

Real example: A 2G mast on top of a Scottish highland can reach across a valley 20 km away. A 5G millimeter-wave site on the same location would only reach 300 metres due to signal attenuation and interference.

3G (UMTS): The Urban Standard

Frequency: 2100 MHz (primarily)

Coverage distance: Typically 1–3 km in urban areas; up to 5 km in optimal rural conditions

Why shorter range? Higher frequency (shorter wavelength = about 14 cm) means signals do not diffract around obstacles as well. They get absorbed by buildings and trees more readily.

4G (LTE): The Balanced Approach

Frequencies: 800 MHz, 1800 MHz, 2600 MHz (operators use multiple bands)

Coverage distance: 2–5 km depending on which band

Why variable? 4G uses different frequencies strategically:

- 800 MHz band (lowest): Best coverage, reaches 4–5 km; used for nationwide coverage

- 1800 MHz band: Medium range, 2–3 km; good balance of coverage and capacity

- 2600 MHz band (highest): Shortest range, 1–2 km; used only in dense urban areas for capacity

5G (NR): The Complexity Problem

5G is split into two sub-bands with radically different properties:

Sub-6 GHz (mainly 3.5 GHz in the UK):

- Coverage distance: 1–3 km

- Speed: 100–500 Mbps in real-world conditions

- Deployment: Primary 5G band for nationwide coverage

Millimeter-Wave (26 GHz and 40 GHz):

- Coverage distance: 100–300 metres (sometimes only 50 metres indoors)

- Speed: 1–10 Gbps (theoretical); 500 Mbps to 2 Gbps real-world

- Deployment: Only in high-traffic urban hotspots (stadiums, shopping centres, business districts)

- Challenge: Requires small cells every few hundred metres; massive infrastructure cost

⚠️ The 5G mmWave Reality: Operators love to advertise 5G speeds, but in most places, you are getting sub-6 GHz 5G (not mmWave). Real mmWave coverage is still very limited in the UK—mainly central London, Manchester, Birmingham, and a few other major cities. If you see “5G” on your phone but are not in a city centre, you are likely on sub-6 GHz, not the “super-fast” mmWave everyone talks about.

9. Network Protocols and Standards: The Language of the Network

Mobile networks communicate using standardised protocols. Each generation has its own:

- GSM (2G): Global System for Mobile Communications; defined signal formats, authentication, and handoff procedures for 2G

- UMTS (3G): Universal Mobile Telecommunications System; introduced wideband code-division multiple access (W-CDMA) for higher capacity

- LTE (4G): Long-Term Evolution; introduced OFDMA (Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access) for efficient spectrum use

- NR (5G): New Radio; entirely new air interface designed for flexibility, low latency, and massive device connections

These protocols are defined by 3GPP (the 3rd Generation Partnership Project), an international standards body. When a new protocol is defined, equipment manufacturers worldwide build equipment to that standard, ensuring interoperability.

Network Slicing (5G Innovation):

One of 5G’s most powerful features is network slicing. The core network can be divided into virtual sub-networks, each optimized for specific use cases:

- eMBB slice: Enhanced Mobile Broadband (for video streaming)

- URLLC slice: Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communications (for autonomous vehicles and surgery)

- mMTC slice: Massive Machine-Type Communications (for IoT)

This is not yet widely deployed in the UK, but it is the future. By 2027–2028, expect operators to start marketing service tiers based on which network slice you get.

10. Security & Privacy: How Your Data Is Protected (And Where It Is Not)

Mobile networks implement security at multiple layers:

Layer 1: Authentication (We Already Covered This)

Your SIM card proves to the network that you are authorized. This prevents someone else from impersonating you.

Layer 2: Encryption on the Air

Data transmitted between your phone and the tower is encrypted using protocols like AES (Advanced Encryption Standard). This prevents someone from sitting in a van outside intercepting your calls.

Important caveat: 2G encryption (called A5/1) is broken and can be decrypted in real-time by someone with specialized equipment. This is one reason 2G networks are being shut down. 3G and 4G encryption is much stronger.

Layer 3: Internet-Level Encryption

Even with strong network encryption, your data is only as secure as the apps and websites you use. HTTPS websites encrypt data end-to-end, so even if someone intercepts your network traffic, they cannot read it. HTTP websites (without the S) do not encrypt, so your data can be read by anyone.

Threats Still Exist:

- SIM jacking: Someone poses as you to your network provider and gets them to transfer your number to a new SIM in a different phone. This can be used to access your email, bank account, etc. It happens hundreds of times per year in the UK.

- Fake base stations: Someone sets up a fake cell tower (called a “Stingray”) that your phone connects to instead of a real tower. Law enforcement uses these in investigations; criminals sometimes use them for interception.

- Man-in-the-middle attacks: Someone intercepts your data between the tower and the network. Encrypted apps like WhatsApp protect against this; unencrypted protocols like HTTP do not.

✓ Best practices: Use https websites whenever possible. Use encrypted messaging apps (WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram). Do not reuse passwords across sites. Enable two-factor authentication on important accounts using an authenticator app (not SMS, which can be intercepted via SIM jacking).

11. UK Mobile History: From Vodafone 1985 to VodafoneThree 2025

The UK’s mobile story is a fascinating journey through technology and business.

1985: The Beginning

Vodafone (spun off from Racal Electronics) launches the first cellular network in the UK. It is analog, brick phones, no text messaging, no data. Calls cost about £2–3 per minute (in today’s money, that is about £8 per minute!).

1989: Cellnet Launches

Cellnet (owned by BT) becomes the second network. Competition begins.

1991–1992: 2G Revolution

Both networks launch digital 2G GSM service. Suddenly, you can get decent coverage, text messaging becomes a thing, and prices fall. This is when mobile phones become ubiquitous.

1993: One-2-One and Orange

Two new networks launch: One-2-One (later T-Mobile) and Orange. The UK now has 4 operators. Intense competition drives innovation and prices down.

2000s: 3G Rollout

Vodafone, Cellnet (renamed O2), One-2-One (renamed T-Mobile), and Orange all launch 3G networks. Three (the company) launches directly with 3G—no 2G service. This is bold and risky but becomes their identity.

2010s: 4G and Consolidation

EE (formed from a merger of Orange and T-Mobile) launches first 4G network in the UK (2012). Over the next decade, consolidation happens: EE acquired by BT, Vodafone and Three discuss mergers, Virgin Media acquires O2.

2025: The Big Merger

In June 2025, Vodafone and Three merge (after years of failed attempts). This reduces the UK from 4 major operators to 3: EE, O2 (now Virgin Media O2), and VodafoneThree. This is controversial—consumer groups worry about reduced competition. Ofcom is still investigating.

Key Motorola Moments:

Early UK mobile users remember these iconic Motorola phones:

- DynaTAC 8000X (1983): The original “brick” phone. Huge, heavy, £4,000. Battery life: 30 minutes. Aspirational status symbol.

- MicroTAC (1989): First flip phone. Revolutionary at the time.

- StarTAC (1996): The clam shell design. Iconic. Used by James Bond in “Tomorrow Never Dies.”

These phones shaped the visual identity of 1980s and 1990s business culture.

12. Myths & Reality: Debunking Mobile Network Falsehoods

Myth 1: “5G is not real.”

Reality: 5G is absolutely real. Hundreds of millions of devices worldwide are connected to 5G networks. The UK has 3G coverage in all major cities. However, coverage is still rolling out, and most claims about “super-fast 5G” are misleading because most people are getting sub-6 GHz 5G (100–500 Mbps), not millimeter-wave 5G (which is much faster but has almost no coverage).

Myth 2: “5G causes cancer.”

Reality: There is no scientific evidence that 5G causes cancer. The World Health Organization, the UK’s Health and Safety Executive, and the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection all confirm 5G is safe at approved power levels. 5G uses non-ionizing radiation (radio waves), which do not damage DNA. If 5G frequencies caused cancer, they would have caused cancer when used in radar systems, wireless broadband, satellite communications, and countless other applications for decades.

Myth 3: “More bars = faster speeds.”

Reality: Signal strength (bars) and speed are loosely related but not the same. You can have 4 bars of signal on a congested 4G tower and get slower speeds than 2 bars on a less congested 5G tower. Bars show signal strength; speed depends on signal quality, network congestion, and the technology being used.

Myth 4: “2G is completely dead.”

Reality: 2G is being phased out but is not gone yet. UK operators are shutting it down by 2030. This is creating huge challenges: old alarm systems, car emergency call buttons, payment terminals, and medical devices still rely on 2G. Expect disruptions in 2026–2030.

Myth 5: “You should turn off 5G to save battery.”

Reality: Modern 5G consumes similar power to 4G (or sometimes less). Turning off 5G will not significantly extend battery life. The real battery killers are screen brightness, location services, and background app refresh.

13. The Internet of Things: Cellular Networks Supporting Connected Devices

Mobile networks are increasingly carrying non-human traffic. Smart meters, connected cars, industrial sensors, and wearables all rely on cellular connectivity.

NB-IoT (Narrowband IoT):

Designed for low-power, long-battery-life IoT devices. Typical use cases: smart meters, asset tracking, environmental sensors. Data rates are low (around 250 kbps), but devices can run for years on a single battery.

LTE-M:

Similar to NB-IoT but with slightly higher data rates. Used for more demanding IoT applications like remote monitoring.

5G Implications for IoT:

5G’s network slicing capability allows operators to dedicate virtual networks to IoT traffic, ensuring reliable connectivity for critical applications (autonomous vehicles, remote surgery, industrial control).

14. Frequently Asked Questions

How does my phone know which tower to connect to?

Your phone constantly scans for nearby towers and measures signal strength. It automatically connects to the tower with the strongest signal (or by negotiation, the least congested tower). As you move, your phone hands off from one tower to another seamlessly—this is called a “handoff” and typically happens every 1–2 minutes while driving.

Why is my signal weaker indoors?

Radio waves are absorbed and reflected by buildings. Concrete and metal are especially reflective, causing signal loss. Modern buildings with lots of glass, steel, and concrete can lose 10–20 dB of signal compared to outdoors—equivalent to being 5–10x farther from the tower. This is why operators deploy small cells indoors in shopping centres and office buildings.

What happens when I cross borders (e.g., UK to France)?

Your phone automatically searches for networks available in the new country. It prioritizes networks with roaming agreements with your home operator. You will connect automatically (usually) and roaming charges will apply. Some operators’ phone plans include European roaming; others charge per day or per MB.

Why do I lose signal in the same place every day?

Likely causes: (1) Network congestion at a specific time (e.g., during rush hour, everyone connects at once); (2) Weather (rain and storms degrade signal); (3) Interference from nearby devices (microwave ovens, wireless routers); (4) Backhaul congestion (the fiber connection to that tower is overloaded). Contact your operator if this is persistent—they can investigate.

Is eSIM better than a physical SIM?

For most people, not particularly. Both are equally secure and reliable. eSIM’s main advantage is convenience (no need to swap physical cards) and the ability to have multiple numbers on one phone. eSIM is better if you travel frequently or need both a work and personal number. Physical SIM is better if you swap phones often (activation is faster).

What is “network slicing” and why should I care?

Network slicing is a 5G feature that creates virtual sub-networks optimized for different uses. In the future, you might buy different “slices” depending on your needs: a fast slice for streaming, a low-latency slice for gaming, or an IoT slice for smart home devices. This allows operators to offer more granular service tiers and guarantees.

Can my location really be pinpointed within minutes via triangulation?

Yes. Emergency services can locate you using triangulation in urban areas (50–200 metres accuracy). In rural areas with sparse towers, accuracy drops to 500–2,000 metres. This is why 999 calls include location even if you cannot provide an address. The network automatically shares your location with the emergency service.

Will 2G really be completely shut down?

Yes, UK operators are scheduled to shut down 2G by 2030. This will affect millions of devices: older phones, alarm systems, car emergency call buttons, ATMs, and medical devices. Operators are preparing migration strategies, but disruptions are expected during the transition.

15. Technical Glossary

- IMSI

- International Mobile Subscriber Identity. A 15-digit unique number stored on your SIM card that identifies you to the network. Like your digital passport.

- IMEI

- International Mobile Equipment Identity. A 15-digit number that uniquely identifies your specific phone hardware (not the SIM). Used to track and block stolen phones.

- SIM Card

- Subscriber Identity Module. A small chip that stores your identity, authentication data, and billing information. Required to connect to a mobile network.

- eSIM

- Embedded SIM. A rewritable digital SIM built into modern phones. Allows network switching without physical card swaps.

- MVNO

- Mobile Virtual Network Operator. A company that leases network access from a major operator and resells it under their own brand (e.g., Tesco Mobile). MVNOs do not own infrastructure.

- MNO

- Mobile Network Operator. A company that owns cellular infrastructure (towers, spectrum, core network). In the UK: EE, O2, VodafoneThree.

- Spectrum

- Radio frequencies allocated by government for mobile network use. Auctions determine which operators get which frequencies. Valuable, expensive, and limited.

- Small Cells

- Low-power base stations (femtocells, picocells, DAS) with short range (100m-1km). Used to fill coverage gaps and boost capacity in dense areas.

- EPC

- Evolved Packet Core. The core network architecture for 4G LTE. Handles routing, billing, authentication, and mobility.

- 5GC

- 5G Core. The new core network architecture for 5G. More flexible than EPC; supports network slicing and edge computing.

- Backhaul

- Fiber optic cables connecting cell towers to the network core. The “pipes” carrying all data from your phone to the internet. Often the bottleneck.

- Handoff

- The process of your phone switching from one cell tower to another as you move. Should be seamless but can cause brief audio drops if poorly executed.

- A5/1

- The encryption standard used in 2G networks. Now considered broken and insecure. Can be decrypted in real-time with specialized equipment.

- OFDMA

- Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access. The technology used in 4G and 5G to divide the spectrum into many sub-channels, allowing multiple users to share the same frequency efficiently.

- Network Slicing

- A 5G feature that divides the core network into virtual sub-networks, each optimized for specific use cases (high-speed broadband, low-latency communications, massive IoT).

- NTN

- Non-Terrestrial Network. Satellite-based cellular coverage. Emerging technology that will allow your phone to connect to satellites in areas without terrestrial coverage.

- mmWave

- Millimeter-wave. 5G frequencies above 24 GHz (26 GHz, 40 GHz in the UK). Ultra-fast but very short range (100–300m). Limited deployment in UK.

- Sub-6 GHz

- 5G frequencies below 6 GHz (mainly 3.5 GHz in the UK). Longer range than mmWave but slower speeds. Primary 5G band for nationwide coverage.